I. Introduction

II. AD 33/34-65

1. Phase 1

2. Phase 2

3. Phase 3

4. Phase 4

5. Phase 5

2. Paul the Jew

III. AD 65-100

A. Important Early Christian Centers of Growth

1. Palestine

2. Syria

3. Asia Minor

4. Rome

5. Egypt

B. The Church's Distinguishing Features

1. Septuagint Remains Christian Bible

2. Maintains Eschatological Expectations

3. Relationship with Rome Becomes Increasingly Strained

4. Continues To Clash with Judaism

5. Removal from Jerusalem Brings Universality

6. Develops Organizational Structure

7. Worship Takes On Regular Formal Patterns

8. More New Testament Documents Written-Canon Developed

9. Increasingly Fights Gnosticism

10. Develops confessions of Faith

11. Clarifies Thinking about Jesus and Matters of Christian Faith

12. Develops Fuller Christology

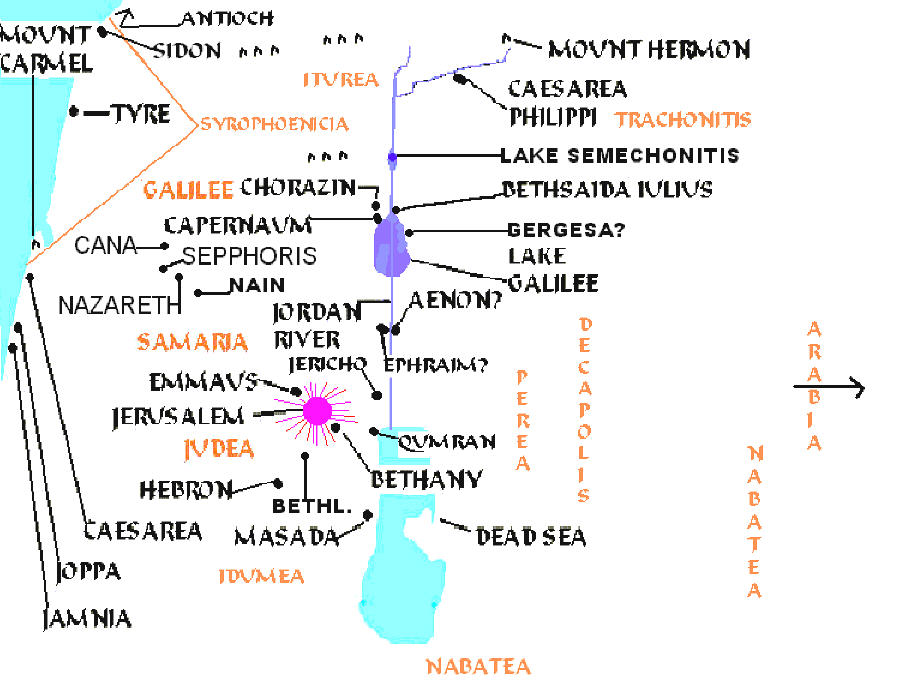

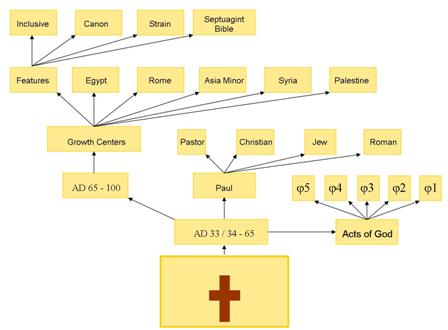

Figure 1 First-Century AD Palestine-Church Growth

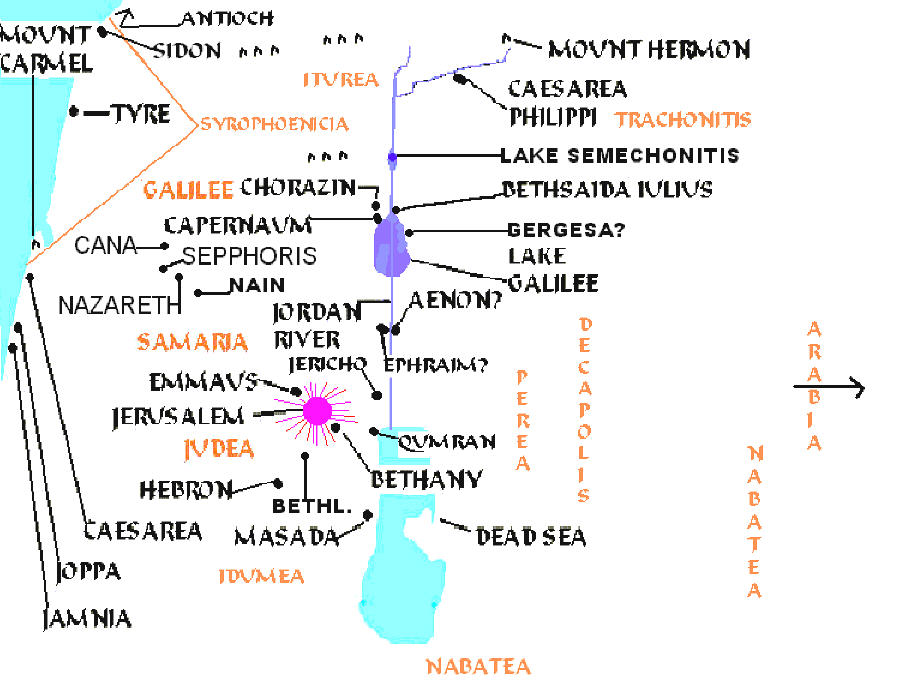

Figure 2 Sadducean-Pharisaic Burden

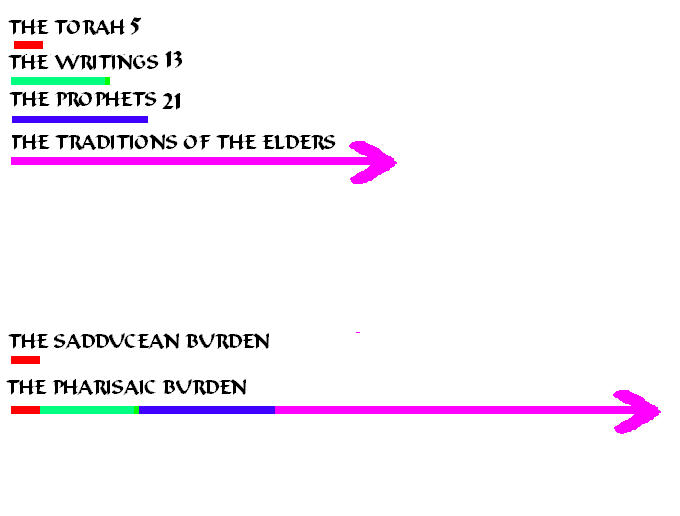

Figure 3 Jehovah God’s Church Structure

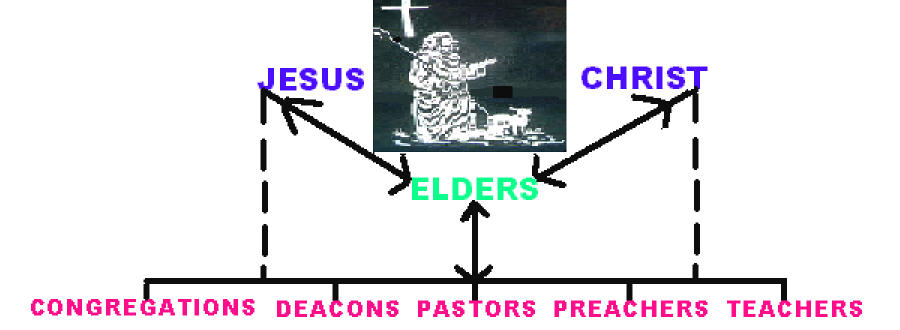

Figure 4 The Unfolding of Christendom

Figure 5 The Fertile Crescent

Table 1 Themes of Stephen’s Speech

Table 2 Missionary Journeys of Paul

Table 3 First-Century AD Roman Emperors

Table 4 Platform Christian versus Jewish Missionary AD 70.

Table 5 Admixtures of Roman Syncretism in the First-Century AD

This study was motivated by a lecture series on New Testament history given by Dr. Lloyd Melton.

Earliest Christianity can be divided into two significant periods:

(1) That period from the resurrection and ascension of our Savior until the death of Paul the Apostle (c. AD 33/4-65),

(2) That period from the death of Paul until the end of the first-century AD (c. AD 65-100).

This study is interested in both of these periods (Fig. 4—the various blocks in the figure are the objects of this study).

Our Savior’s resurrection must have hit the apostolic band like a shock wave, for it helped instill in them a working faith that transformed this group into undaunted messengers of the Gospel—and so changed human history. It is fair to say that the impact of the Gospel has no parallel in human history, as measured by its holy influence on people, its pervasiveness throughout the globe in spite of quite mean beginnings, its staying power in the face of time, onslaught, and competition (e.g., Rome, Judaism), and so on. When the Holy Spirit descended upon the first believers at Pentecost (Acts 2:1-4) their joy over our Savior’s resurrection and their faith in Him were ignited by a divine power that set in motion the building of the Christian Church. In the skillful hands of our God, these men and women became instruments toward that end—so His good purposes for humankind might come to fruition by way of a Spiritual Temple comprised at the outset of this fledgling band (concerning the role of women in early Christendom a comprehensive study is presented by Dr. Witherington-Women in the Earliest Churches).

Whereas the first-half of the first-century AD was a relatively stable period for the Roman Empire, the latter half was a characteristically turbulent one. An adolescent, not yet seventeen, assumed absolute control of this awesome empire, largely through the machinations of his unbalanced mother—Agrippina the Younger (“Agrippina the Younger”). That boy, whom Agrippina induced her husband (and uncle) Claudius I, then emperor, to adopt was Nero. Agrippina was the sister of the third Roman emperor Gaius (or Caligula, which is a nickname meaning “Bootee,” a soldier’s boot, Reicke 237), and a great granddaughter of the first Roman emperor Augustus (table 3). Nero's early reign was greatly influenced by Agrippina. However, the prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Afranius Burrus, who was instrumental in having Nero proclaimed Caesar, and Seneca, the Stoic philosopher, soon persuaded Nero to act on his own. This ultimately resulted in Agrippina's “retirement” in AD 56; her murder came at the hands of Nero in AD 59, possibly because of meddling in one of his romantic affairs. From AD 56 to 62 Burrus and Seneca were in effect the rulers of the empire—they left Nero to indulge his own pleasures while they ran the empire. It seems that Nero's irresponsibility and overindulgences gave way to depravity after the murder of his mother. In 62 Burrus died, and in 63 Seneca was ousted (Reicke 241), leaving Nero devoid of sound counsel. Revolt in the empire—Armenia/Parthia-AD 58, Britain-AD 60, and Judea-AD 66, together with a conspiracy to overthrow Nero that had a great diversity of patrons (e.g., Piso-AD 65) as also a constituency of provinces that were generally growing disillusioned with Nero and of financing his extravagances, some of which were purported to be several times the annual cost of maintaining the army ("Nero"), were ominous signs for Nero and for Rome's stability. Indeed, all this ultimately contributed to Nero's demise by suicide in AD 68, whereupon followed a destabilizing power struggle that resulted in four different emperors in just one year (Galba, Otho, Vitellius, Vespasian, AD 68-69). In the midst of this turbulence Rome burned, literally. The setting of the great fire of AD 64, which largely consumed the city, was pinned on Nero by the Roman populace. They accused him of setting the fire as a means to modernize the city along Hellenic lines in its reconstruction. In response, Nero shifted the blame to the Christians ("Nero"). Thus began the first state-sanctioned persecution of Christians; up until that time Christianity was considered a sect within Judaism, which was a licensed religion by Rome. As such, Christianity had enjoyed the same privileges and freedom of worship as did Judaism (Melton). It is difficult to determine accurately how widespread this persecution of Christians was within the Roman Empire. It is probably fair to suppose that it was generally contained to Rome and its surroundings, with those places in the empire where Nero's cronies sought to find his favor being the exception. In this scenario one can imagine pockets of state-sponsored persecution throughout the empire, with the heaviest in and around the city of Rome. It is in this wave of persecution around AD 65 that the Apostles Paul and Peter were likely martyred (Cruse 63). The books of Hebrews 1:1ff and 1 Peter 1:1ff may have been written, in part, for Christians who were caught up in this wave of persecution, to help them in their trials; to help them understand what they were suffering, and why; to help them resist the temptation to alleviate their suffering by returning to the safety of Judaism, thus compromising their Christian faith (Melton). So began the latter third of the first-century AD for Christians—steeped in blood—and so it would end. For the persecution that Nero almost “halfheartedly” started, another tyrant, the emperor Domitian, systematized with megalomaniacal resolve (some scholars hold that there is not sufficient Roman evidence to unambiguously suggest that Domitian systematically persecuted Christians). Domitian was a great threat to the Christian Church in the first-century AD. He proclaimed himself to be a god and decreed that all people throughout the empire engage in emperor worship on Sundays—the emperor's day—as a patriotic gesture. This of course penalized only one group—Christians—because Jews were exempted by way of the license of their religion; for most, if not all the rest obligated by Roman law, it was viewed as no more than a simple patriotic gesture, and they probably took it in stride. But for Christians, a distinct religion not under the protection of the Jews’ license, and bound by the confession ‘Jesus [alone] is Lord’ (1 Cor. 8:6), and the first and second commandments (Exod. 20:3-5), it was a great test of faith. Many Christians were martyred under Domitian; many others were jailed or persecuted in other ways. The book of Revelation 1:1ff was probably written for Christians in Asia Minor, in part, in response to this suffering, to help them stand fast against the temptation to alleviate their suffering by succumbing to emperor worship ("anything goes" Asia Minor was a hotbed of emperor worship at that time). This was a heavy, sorrowful time for a Church that had just barely gotten out of the gate. As we shall see, reasons abounded for the Christian Church to founder and not make it out of the first-century AD intact.

The Book of Acts 1:1ff relates to us the history of the inception and early growth of the Christian Church, a history that is sometimes referred to as theological history, for it has been said, 'the true “acter” [as in action] in Acts is not Paul, or the Apostles, or the Church...the true “Acter” in Acts is Jehovah God’. In the broader sense, Luke, in the Book of Acts, seems to convey a picture of how God established the Christian Church through the ministry of His Son Jesus (c. AD 30-33/34; Matthew 1:1ff, Mark 1:1ff Luke 1:1ff, John 1:1ff), and then gradually moved it out of its narrow, provincial, Jewish origins in Jerusalem and Judea, and thrust it into the heart of the pagan Greco-Roman world, largely through the ministry of Paul the Apostle (c. AD 33/34-65). Studying Acts we come to understand that God did this so that the Church might bear witness to the death and resurrection and deity and person of Jesus (Acts 1:8), and call people to repentance (Acts 2:38) and new life in Jesus (2 Cor. 5:17). Luke uses the history of the spread of the Church to show the greatness and power of our God, and to illustrate that God's intention all along, as finally realized in the Gospel, was to come into the world in Jesus—for all peoples (“Covenant People”)–all of whom are in need of His grace (Melton). So the Book of Acts is more than raw history, it is also a view into the intentions and workings of Jehovah God as related by the birth and spread of the Christian Church, a view of mercy and grace, of majesty and power…in action.

The first phase of the Christian Church's history is heavily Jewish. Jews and Judaism were an integral part of the fledgling Church. For example, Jesus was born into a Jewish bloodline; the twelve apostles were Jewish; the very first part of Jesus' and the disciples' ministry was limited to Jews; the setting was Jerusalem and Judea in the early days (admittedly, it soon shifted to Gentile Galilee); the early believers, largely Jewish, were celebrating the Jewish feast of Hag Shavuot[1] when the Holy Spirit came upon them seven Sundays (some fifty-days) after the death, burial, and resurrection of our Savior. The early chapters of Acts relate a very Jewish environment—the mindset of the early Church was Jewish, heavily steeped in Judaism. As such, the apostles and early Christians probably did not think of themselves as belonging to a distinct sect removed from Judaism; rather, they likely saw themselves simply as completed Jews—Jews who believed that the Messianic promises of the Old Testament had been fulfilled in Jesus—the One in whom they now believed. For example, at Pentecost Peter preaches quoting Old Testament passages, but shows how they have been brought to fruition in Jesus Acts 2:14-36). To the early believers their "Christian" experience probably seemed like a logical and natural extension and expression of their Jewish experience (Melton). They likely kept the Sabbath, attended the synagogue, studied the Torah, practiced the acts of piety and almsgiving required of a good Jew, and so forth. And yet, at the appropriate time they undoubtedly gathered as a group of believers in Jesus and broke bread, and celebrated the Resurrection. In other words, they were on the face of it Jews in every way, but they were Jews that believed in Jesus Christ. Similarly, the Church's outreach early on was to Jews. Peter's sermon on Pentecost largely addressed a Jewish audience—Jerusalemites and visiting Jews from the Diaspora there to fulfill their (Pentecostal) duties in the temple. Thus both the makeup and outreach of the early Christian Church was heavily Jewish. This is the distinguishing characteristic of phase 1 of the Church's history. If one were to view the phases of the Church's history as waves on a pond caused by a pebble hitting the surface of the water (Melton), phase 1—the Jewish phase—would be the epicenter, itself located in Jerusalem (Fig. 1). This view helps keep in focus the dynamics of our God's workings with the Church—after establishing it in a thoroughly Jewish setting, He set out to extend it into the heart of the pagan Greco-Roman world for the ultimate benefit of all peoples everywhere, for all time. So, as we shall see, the next phases—the spreading out of the outreach waves—successively spread the Church further beyond its narrow, provincial, Jewish origins.

The first wave to travel beyond the epicenter of provincial Judaism, our phase 2 in this outline, comes by way of the person of Stephen—who was a Hellenistic Jewish Christian. It is reasonable to assume that Hellenistic Jewish Christians promoted the theological doctrine of inclusivity (essentially, that Jehovah God never intended for the Jews only to be His chosen people—that all people were His chosen people—as distinctly evidenced by the atoning death of Jesus for all who come to repentance and believe in Him). For our purposes, the doctrine of inclusivity is an important part of phase 2, and it is reflected here in Stephen. What we see in Stephen is not just a Jewish Christian, but a Hellenistic Jewish Christian, one who is removed a bit further from provincial Judaism—not a typical orthodox Palestinian Jew. This character of Stephen is materially borne out by the major themes of his address to the Sanhedrin after his arrest (Tab. 1). Nikolaus Walter points out that according to Luke's terminology, "Hellenists" were all non-Greeks that spoke Greek, but that the term also referred to Diaspora Jews who held differing views regarding the Torah, the Temple, and even Jesus, than did Stephen's group (Walter 40); one must add here that groups of Jewish Hellenists also differed according to their degree of nationalistic fervor. The diversity within Hellenistic Judaism becomes apparent against the backdrop of Acts 6:9-10, where Stephen becomes engaged in debate with men from the Synagogue of Freed Slaves, who were Hellenistic Jews from Cyrene, Alexandria, Cilicia, and the province of Asia. They were essentially Diaspora Jews that were allowed to return home to Jerusalem/Judea—it is significant that returning Diaspora Jews gathered according to Diaspora nationality at home in Jerusalem (their distinctive Hellenistic Judaism was not something that the Palestinian environment could easily erase). So we see here, at different turns, viable arguments for a diverse Hellenistic Judaism, a pluralistic Hellenistic Judaism in the period under study. According to Walter, Hellenistic Judaism

"…refers to a Judaism whose own thinking has been—in part unconsciously, but to a large degree quite consciously and knowingly—shaped by Hellenistic thinking and a Hellenistic ethos or ‘worldview'; a Judaism which consciously took part in the intercultural encounters of late antiquity, not refusing in any way to do so; a Judaism which was therefore not only exposed, in a more or less strong and more or less unperceived way, to the general Hellenistic influences of the era, and so was subordinated to them" ( Walter 41).

A review of the Alexandrian Jewish literature bears this out. It betrays a general expression on the part of these Jewish authors that is generally directed toward making intercultural contact; toward communicating distinctly Jewish ideas that are nevertheless couched in distinct Hellenistic intellectual motifs—yet without compromise of Jewishness. In the aggregate it is an expression that conveys the idea that the Torah is a universal Law for all peoples of the world. In that vein, the writings, in accordance with their style and through either open or hidden Scripture allusion, urge the reader to pursue the traditional basis of Israel's faith, which is embodied in the Torah, and understood as divine wisdom, as in, for example, the works of Aristobulus, Philo, the anonymous Alexandrian-Jewish Hellenistic author of the Wisdom of Solomon, the authors of the Sibylline Oracles, et al. That idea, as transmitted so keenly in the literature, at least, helped pave the way for the Gospel of Jesus Christ to spread rapidly amongst the Hellenistic Jewish and Gentile Greco-Roman world. Alexandria represents the only center of literary development in the Jewish Diaspora of the Hellenistic Greco-Roman world with extant texts, themselves widely representative of Hellenistic intellectual motifs at the birth of primitive Christianity, and is therefore an important window into Hellenistic Judaism as it existed at that time. Stephen and his group probably represent a group of Jews that returned to Judea (Jerusalem) from the Diaspora who brought their particular variety of Hellenistic Jewishness with them. They probably held the view—which had become gradually impressed upon them by way of their Hellenistic exposure, and which they internalized—if the Torah was indeed of divine origin, it must properly belong to all human beings created by God. This particular view within pluralistic Hellenistic Judaism—Torah, common property of all humanity—helped pave the way, through its broadcast, whether by literature or otherwise, for the rapid spread of the Gospel in the Hellenistic Greco-Roman world. For that world, through that view, became familiar with, and internalized, an integral part of the Gospel; namely, the Torah, or universal Law. After all, the Fall notwithstanding, the Cross was necessary for no other reason than to provide a means of atonement for breaches of that Law; and atonement must necessarily precede the peace of salvation (Rom. 6:23, Rom. 5:12-21). Further, they undoubtedly concluded that the harsh Torah-based legislation particular to Pharisaic Judaism—that was characteristic especially of Palestinian Judaism, and hence many of Jesus' initial followers, and which also some circles within Hellenistic Judaism embraced as the only means of salvation—ran counter to Jesus' salvific expressions. So they probably preached the good news of the covenant between God and man as outlined in the Torah and first given to the people of Israel, and finally realized in Jesus Christ, to all peoples. Not with any intention of Judaizing the nations in the process, but rather, as an expression of the Torah as universal Law, holy and divine, the quintessence of which is expressly manifested in the Gospel of Jesus Christ, which itself embodies the fulfillment of that Law, from first to last. As a consequence of this broad, comprehensive, "catholic" preaching, Stephen and his group felt the ire of the rest of Judaism (other circles within Hellenistic Judaism in the Diaspora and in Palestine, as well as Pharisaic Judaism in the Diaspora and in Palestine). These other Jews viewed their preaching as blasphemous heresy directed against the divine Torah particularly, as also the Temple and Traditions (Acts 6:11-14); viewed it as an effort that could ultimately supplant the same, and therefore became openly hostile to them (as was, for example, Saul the Persecutor until under divine goading he broke ranks and joined their camp). It is no wonder that the first steps that led to Stephen's death came as a consequence of his disputes with other Hellenistic Jews, who were undoubtedly of this other "exclusive" bent (Acts 6:8-14). The Sanhedrin's mob-killing of Stephen is a window to the impending difficulties that Jewish Christianity would soon face as it witnessed to the inclusive, wide-open nature of the Kingdom of God and so came into direct conflict with the exclusive doctrine of mainstream Judaism. Phase 2 ends with the stoning of Stephen, whereupon is present in a sanctioning capacity Saul the Persecutor (Acts 7:58).

The third phase is marked by a dynamic—organized persecution of the Church. With the blessing of the (Pharisaic/rabbinic) Jewish leadership, Saul set out to ravage the Church (Acts 8:1-3).

"Despite his training under the moderate Gamaliel, Saul must have viewed Stephen's preaching on the law and temple as dangerous and blasphemous heresy. The earliest opposition to the faith had come from the Sadducees, who viewed the proclamation of Jesus as Messiah and Savior as a threat to stability and to their authority. The Pharisees, as illustrated by Gamaliel's attitude, probably viewed the movement as less threatening. There had been no frontal assault on the law, the traditions, and the temple. But many Pharisees must have mistakenly viewed Stephen's message as such an attack. Because of their new perception of the believers, Saul and other Pharisees began to make common cause with the Sadducees against the Christian community" (Niswonger 196).

The Greek verb that Luke uses in Acts 8:3 to describe Saul's pursuit of the Church (ELUMAINETO) suggests that he was behaving like a carnivorous animal ripping and tearing its meat. This obviously caused the believers to flee Jerusalem in all directions for their very lives. Importantly, wherever they resettled they shared the Gospel with those around them thus growing the Church (Acts 8:4). Philip the evangelist, for example, was one of those who fled Jerusalem and evangelized in Samaria (not to be confused with Philip the Galilean disciple [John 1:43ff]—this Philip was a Hellenist, one of the seven [with Stephen] chosen for the Jerusalem widows ministry [Acts 6:1-5]). With Philip we see the Church beginning to move out of Judea and into the Jewish Mediterranean world. This same Philip, under the lead of the Holy Spirit, evangelized and baptized the first African convert (Acts 8:26-38); it is possible that this convert then formed the beginning of a small band of African Christians. Ironically then, with persecution came growth. So Saul and the Jews unintentionally widened the circumference of the waves in phase 3 by persecuting the Church; by the close of this phase the spread of the Church had geographically removed beyond Jerusalem and Judea, though still largely a Jewish entity witnessing to Jews only, but with signs of a shift toward Gentile hearers as well (Acts 11:19-20).

Between phases 3 and 4 comes the account of Saul's conversion (c. AD 33 or 34 Witherington-Paul Quest 306; Acts 9:1-6); and just next Acts gives us a view of the extent of the Church (Acts 9:31; Fig. 1). Phase 4 unfolds by way of the apostle Peter and one God-fearing Gentile named Cornelius (Acts 10:1-6—in that day "God-fearer" was simply a technical term that referred to a Gentile who converted to Judaism but would not commit to circumcision, itself the most identifying sign of a Jew; a God-fearer was a sort of "half-Gentile," "half Jew," so to speak). Now Peter was intensely Jewish; he intently adhered to the exclusive doctrine of Judaism and the ancestral traditions. When God gave Peter a vision to go and preach the Gospel to Cornelius, Peter resisted—not because he was afraid of rejection or persecution by Cornelius, but because Cornelius was a God-fearer. In short, Peter resisted because Cornelius was not a "real Jew" in his eyes—he was an uncircumcised, unclean Gentile, one who any “good” Jew knew had to be avoided (Acts 11:1-3). Peter's mindset here is representative of the struggle that the Church had from the very outset; the struggle to overcome the prejudice rampant in the Judaism of that day—namely, that Jehovah God is the God of the Jews only; that His love and interest concern Jews only, not Gentiles. That is the mindset that Peter and the early Christians inherited from the Judaism out of which they came. It is essentially that prejudice that caused Peter to resist God's call to go to Cornelius and preach the Gospel. Importantly, however, in the vision Jehovah God said in no uncertain terms, 'it is I who will determine what is clean and unclean, not you Peter’ (Acts 10:9-15). As a sort of half-Jew, then, in the person of Cornelius we see the Gospel reaching the very fringes of pietistic Judaism (Melton); indeed, the very fringes of Pharisaic Judaism. And therein lays the significance of phase 4. The Church is here not yet engaged in a full-fledged Gentile mission, but it has now been removed not only geographically from its Judean origins as in phase 3, but theologically as well. The Church is becoming less Jewish and becoming more Gentile (Acts 10:34-48); the Church is approaching the determined, full-fledged Gentile mission that it was soon to undertake by way of Saul the Persecutor turned Paul the Christian Missionary. So ends phase 4—anticipating Paul the Missionary and the Gentile Mission in phase 5.

One of the keys to understanding phase 5 is the increasingly dominant position Antioch of Syria holds as the center for Christian activity—over against the increasingly subordinate position of Jerusalem in Judea in the same respect (Fig. 1-in the figure Antioch lays roughly 30 kilometers east of the Mediterranean Sea, and roughly 500 kilometers north of Jerusalem).

"Of the vast empire conquered by Alexander the Great many states were formed, one of which comprised Syria and other countries to the east and west of it. This realm fell to the lot of one of the conqueror's generals, Seleucus Nicator, or Seleucus I, founder of the dynasty of the Seleucidæ. About the year 300 B. C. he founded a city on the banks of the lower Orontes, some twenty miles from the Syrian coast, and a short distance below Antigonia, the capital of his defeated rival Antigonus. The city, which was named Antioch, from Antiochus, the father of Seleucus, was meant to be the capital of the new realm […]

When Syria was made a Roman province by Pompey (64 B. C.), Antioch continued to be the metropolis of the East. It also became the residence of the legates, or governors, of Syria. In fact, Antioch, after Rome and Alexandria, was the largest city of the empire, with a population of over half a million. Whenever the emperors came to the East they honoured it with their presence. The Seleucidæ as well as the Roman rulers vied with one another in adorning and enriching the city with statues, theatres, temples, aqueducts, public baths, gardens, fountains, and cascades; a broad avenue with four rows of columns, forming covered porticoes on each side, traversed the city from east to west, to the length of several miles […]

The population included a great variety of races. There were Macedonians and Greeks, native Syrians and Phœnecians, Jews and Romans, besides a contingent from further Asia; many flocked there because Seleucus had given to all the right of citizenship. Nevertheless, it remained always predominantly a Greek city. The inhabitants did not enjoy a great reputation for learning or virtue; they were excessively devoted to pleasure, and universally known for their witticisms and sarcasm [...]

Since the city of Antioch was a great centre of government and civilization, the Christian religion spread thither almost from the beginning. Nicolas, one of the seven deacons in Jerusalem, was from Antioch. The seed of Christ's teaching was carried to Antioch by some disciples from Cyprus and Cyrene, who fled from Jerusalem during the persecution that followed upon the martyrdom of St. Stephen. They preached the teachings of Jesus, not only to the Jewish colony but also to the Greeks or Gentiles, and soon large numbers were converted. The mother-church of Jerusalem having heard of the occurrence sent Barnabas thither, who called Saul from Tarsus to Antioch. There they laboured for a whole year with such success that the followers of Christ were acknowledged as forming a distinct community, 'so that at Antioch the disciples were first named Christians '" ( Schaefer).

As Francis Schaefer has pointed out, Antioch was thoroughly saturated with Gentiles in that day; it was grossly different from Jerusalem in this as well as other aspects. Luke points out the fact that the believers were first called Christians at Antioch (Acts 11:26). Given the heavy presence of Gentiles there, it is intuitively obvious that the Gospel was being freely preached to both Jews and Gentiles. So we see therefore at Antioch the unfolding of the great Gentile commission (Matt. 28:19, Acts 1:8). Like the role of Antioch, understanding Paul the Apostle is another key to phase 5, and is discussed as a separate main section just below.

The most significant person in the New Testament apart from our Savior is Paul the Apostle. He is the first great Christian theologian (that is, the first to make intelligible the death and resurrection of Jesus) and the first great Christian missionary. Nearly two-thirds of the Book of Acts is centered on him, and he is responsible for penning thirteen, maybe fourteen, of the remaining twenty-six books of the New Testament. The curiosity is that, given his significance, close examination of all this material reveals scant little about Paul himself: virtually nothing about his birth or childhood, or about his family, his appearance, and so forth. Other sources of information in this regard come from the non-canonical literature and the early Church Fathers (Early Christian Writings). Notwithstanding, the best composite of Paul the person must be drawn by way of Scripture, be that as it may insofar as its extent is concerned, and is possibly as follows:

(1) Paul was born in Tarsus; he likely received a basic education there, and at an early age moved to Jerusalem to study under Gamaliel (Acts 22:3).

(2) He clearly identified himself with the party of the Pharisees (Acts 23:6).

(3) He had a sister (Acts 23:16) and a nephew (Acts 23:20); no conclusions can be drawn about whether or not he was married.

Given the facts available to us today, this is the most reliable composite that can be drawn in these areas. Frankly, such a composite lends very little to our understanding of Paul.

Ben Witherington III in his revealing work The Paul Quest: The Renewed Search for the Jew of Tarsus, shares his understanding of Paul and the world in which he lived. He points out that Paul is best understood relative to the sociocultural forces active in his day. One must avoid drawing conclusions about Paul through both temporal and spatial anachronism; that is, through the lens of "matter-of-fact" post-Enlightenment sociocultural norms, and/or through the lens of "matter-of-fact" Western sociocultural norms. Our best understanding of Paul the person is registered over against the first-century AD Near Eastern sociocultural norms of Paul's day (Witherington-Paul Quest 18-51). Into this framework fits an outline of a reasonable fourfold nature of Paul's identity: Paul the Roman Citizen, Paul the Jew, Paul the Christian, and Paul the Pastor (Melton, Witherington-Paul Quest). We come to understand Paul as best as we can, then, by way of this apt identity. Through this understanding comes by default a reasonable view of the spread of the early Christian Church as concerns the great Gentile mission, that is, phase 5, seeing that Paul was God’s instrument in that regard.

Paul was a man of his Mediterranean world, which world consisted of the Roman Empire in that day. He understood it and knew how to get around in it (Melton). He appreciated its peace, as well as aspects of its culture. He was familiar with Greco-Roman life and reflects popular Greek thought (e.g., Stoicism—Phil. 4:12), as well as a knack for Greco-Roman rhetoric (Galatians) in some of his writings. He seems to be perfectly at home among the Greek philosophers, teachers, and thinkers, as Luke shows us by way of his account of Paul in debate with the same (Acts 17:16-34). Paul was able to make lucid the tenets of Christianity to pagan minds (and to Jews), on their turf, with a rhetoric that incorporated their own thoughts. He was undoubtedly well educated in both Greek thought and matters of Judaism (Witherington-Paul Quest 70). As Jerusalem was Hellenized in his day, this education could have come from there. Paul's birthplace, Tarsus, was absorbed into the new Roman province of Cilicia in 167 BC. Ultimately a university was established there that became known for its exposition of Greek philosophy Niswonger 197). Tarsus was a university town in Paul's day, one wherein all the latest thoughts about man and his surroundings and origins were bandied about. But its influence on Paul may have been negligible as Paul likely did not spend much time in Tarsus; it seems that he moved to Jerusalem at an early age. There is, however, a greater significance to his birth at Tarsus—it made him a Roman citizen, and that was no little thing in the Golden Age of Augustus Caesar (27 BC-14 AD), on through Paul's day just later. With that citizenship came certain rights and privileges that Paul used to his advantage for the advancement of the Gospel. For example, he was able to move about freely in the Empire and access and use the services available to its citizens. In another vein, his citizenship saved his life after the temple incident (Acts 22:25-29), whereupon he was able to use the Roman judicial system to appeal his case to Caesar, and witness all along the way.

Paul was Jewish to the core; he was a Pharisaic Jew, and that meant that the Law was central to his life—he identified himself by the metrics of Law-living; indeed, not the Law only, but the voluminous ancestral Tradition as well (Fig. 2). One aspect to understanding Paul begs recognition of his intimate relationship with the Law and Jewish Tradition because such recognition helps make it obvious that Paul's theological "paradigm shift" from Law to Grace was nothing less than radical. It is hard to appreciate just how gross this shift in belief and ideology must have been for an intense Pharisaic Jew like Paul. The Law, as being one micro-step removed from God Himself, was Paul's center of gravity. Such a change as Paul went through would usually not happen on its own, it was just too extreme in and of itself—let alone that it occurred over a span of just a very short time (admittedly, Paul tarried three years in the Damascus area [Gal. 1:17-18], presumably to pray things through before engaging his mission, but it is obvious from the rest of the story that the seed of change was planted on the Damascus road [Acts 9:1-5]). And one must always remember that this man was a Christian hater and killer, under the auspices of defending God's Law, nay, God Himself, against what seemed to him and the Jews a threatening heresy; indeed, a lie. It is significant that after his conversion Paul recognized that which he had esteemed and revered and labored to uphold—the Law—had actually cursed (Deut. 27:26, Gal. 3:10-13) Jesus, the One whom he now esteemed and revered and labored for. Paul knew the Scriptures—the picture of the Curse of the Law was crystal clear to him. That picture, nailed to a cross in the person of our Savior, must have anguished the converted Paul, in more ways than one; what a jolt for a former Pharisee. It was Jesus on the cross and Jesus on the Damascus road that goaded and awakened Paul the Jew.

We see thereafter how Paul poured out his soul for his fellow Jews, those who had not had the benefit of a Damascus Road to change their center of gravity. Paraphrasing, he prayed, 'how my heart is filled with bitter sorrow and unending grief for my people, my Jewish brethren. I would give up my own salvation—even be cut off from Christ[!]—if that would save them' (Rom 9:2-5). Here speaks a Jew, nay, a completed Jew, a Christian Jew. How deeply Paul identified with Jews; how deeply Paul yearned for his fellow Jews to come to salvation; how deeply Paul loved his fellow Jews. He seems to groan deep, deep in his spirit with the frustration and bewilderment attending the decision of a chosen people who, privy to God's revealed Glory, Plan, Promise, Covenant, and Law, rejected God’s Christ—the very embodiment of what had been revealed. This must have frustrated and grieved Paul to no end, for he knew they were largely not on board. One might suppose that Paul, reflecting on his own demeanor before his conversion, was much weighed down with sorrow and grief owing to their adamant worship of the Law and Ancestral Tradition, above Christ…to their doom.

“For to me, to live is Christ and to die is gain" (Phil. 1:21).

Paul's own words here sum up Paul the Christian better than any others. Paul loved Jesus, and was fully committed to Him. It is true, in Jesus Paul embraced that which Judaism promised, but could not deliver. But more than that, Paul embraced an intimate, personal relationship with a willing Jesus. And all the other identifying features of Paul the Christian flowed from that, naturally. From that flowed his missionary zeal, his personal sacrifice for the sake of the advancement of Christ's Gospel, his life of example and endless ministry, and finally, his martyrdom unto eternal fellowship with his Messiah and Friend.

Paul the Pastor, indeed, Paul the missionary Pastor, comes out in his letters to the churches that he either established outright and/or helped to establish during his journeys (Tab. 2). His letter-writing began (New Testament Canon: Table 1) after he had been a Christian for approximately fifteen years (c. AD 48/49; Witherington-Paul Quest 73). He had had some time to grow in his Christianity and contemplate the things that had happened to him since the Damascus Road experience. And his letters reflect that; he wrote not as a neophyte, but as an authoritative Christian theologian, and pastor, responding to the particular situations that he was made aware of in a given church/faith community. His letters were not theological treatises, and we can be sure that he had no notion that they would be pored over for centuries on end. They were simply composed to address situations that any pastor would feel burdened to respond to, in any age, in order to see God's interests served. Paul was passionate about his people, even indignant when they failed, but he never ceased to be a pastor to them. It probably serves us best to prayerfully read these letters with an eye to the particular situation that Paul was responding to when he addressed congregations that had either gotten into trouble, or simply posed some problem or challenge—and then try to absorb Paul's response, a response which came to him by way of the Gospel that he received from our Lord Jesus Christ. So we see, finally, that Paul not only lead the mission to the Gentiles, but passionately and tenderly shepherded the flock—like a good shepherd.

"Because of the veil of darkness covering the era from about A. D. 65 to 150, the exact boundaries of Christian expansion can only be approximated. There simply are not sufficient extant documents to bridge the gap of our ignorance about early Christian history for a period of about eight decades after the events recorded in Acts" (Niswonger 279).

"Christ established a Church and, in a variety of parables, sketched many of the features of its character and history, all of which point to something external and perceptible by the senses. It is the 'house built upon a rock ' showing the security and permanence of its foundation, and 'the city set upon a hill ' indicating its visibility. Its doctrine works in the three great races descended from Noe's sons like the leaven hidden in three measures of meal, silently, irresistibly. It grows great from humble beginnings, like the mustard seed. It is a vineyard, a sheep-fold, and finally a kingdom, all of which images are unintelligible if the bond that unites Christians is merely the invisible bond of charity. The old distinction between the body and soul of the Church is useful to prevent confusion of ideas. Christian baptism constitutes membership in the Visible Church; the state of grace, membership in the Invisible. It is obvious that one membership does not necessarily connote the other" (Keating).

That membership materially manifested itself at key places within the Roman Empire: Palestine, Syria, Asia Minor, Rome, and Egypt (“Roman Empire-Map”); we discuss each in turn next. Given the scarcity of witnesses in the period under study, our discussion of some of these locales falls just outside the latter-third of the first-century AD.

The mother-church, where it all began, belonged to Palestine—to Jerusalem (Fig. 1), and it continued to be immersed in Pharisaic Judaism throughout this period (ritual cleanness, circumcision, fasting, Sabbath observance, synagogue attendance, Torah study, etc.) and never really engaged in any kind of substantive Gentile mission. James, surnamed the Just—the half-brother of Jesus (“James the Just”)—became the first bishop of the Jerusalem Church; in general, the family of Jesus became significant leaders of that church such that, together with the presence of the apostles, the Jerusalem Church had a ring of authority about it. We see this when upon Paul's return from his first missionary journey (Tab. 2), Antioch appeals to Jerusalem for authoritative counsel concerning the issue of Gentile circumcision as a requirement for entry into Christianity (the Jerusalem Council—Acts 15:4-20).Though the issue was resolved, that is, the council decided that no, Gentiles do not have to be circumcised or yield to Jewish Law in order to become Christians, it remained a real problem (Gal. 2:11-14) throughout the rest of the first-century AD, especially in the Jerusalem Church; the believers at Jerusalem were uncomfortable admitting uncircumcised Gentiles into their ranks. It is significant that Peter was commissioned to evangelize the Jews while Paul was commissioned to evangelize the Gentiles by that same council (Gal. 2:1-10). So the Jerusalem Church retained its Jewish flavor and became correspondingly weak (Acts 11:29, 1 Cor. 16:1-3) and of less importance within Christendom as the first-century unfolded.

Syria's prominence as a great center of growth in early Christianity is inextricably linked with the prominence of Antioch as a melting pot of civilization and center of government; Antioch was a thoroughly Hellenized cosmopolitan intersection linking the mother-church in the south with the Greco-Roman West and the Perso-Babylonian East. The persecution that followed the martyrdom of Stephen helped spread Christianity to Antioch very early in the Church's history (Acts 11:19-20); Antioch then became the springboard for the great Gentile mission, not only to the Syrian cities and provinces, but also westward and eastward to Greco-Rome and Perso-Babylonia, respectively (“The Acts of God”).

"As Jewish Christianity originated at Jerusalem, so Gentile Christianity started at Antioch, then the leading center of the Hellenistic East, with Peter and Paul as its apostles. From Antioch it spread to the various cities and provinces of Syria, among the Hellenistic Syrians as well as among the Hellenistic Jews who, as a result of the great rebellions against the Romans in A. D. 70 and 130, were driven out from Jerusalem and Palestine into Syria. The spread of the new religion was so rapid and successful that at the time of Constantine Syria was honeycombed with Christian churches [Constantine reigned AD 306-337]. The history of the Christian Church in Syria during the second and third centuries is rather obscure, yet sufficient data to furnish a fair idea of the rapid spread of Christianity in Syria have been collected by Harnack in his well-known work 'The Mission and Expansion of Christianity in the First Three Centuries' (Eng. Tr., 2nd ed., London 1908, vol. II, pp. 120 sqq.)" (Ouissani)

Paul's missionary journeys (Tab. 2) were largely centered on Asia Minor, a region which embodied the syncretism of the Greco-Roman world in all its fullness (“Syncretism”, Tab. 5). This was true of almost any city there. As a consequence of Paul’s labors, “Asia Minor and the Aegean coast of Greece came to hold the largest concentrations of Christians in Christendom from AD 180 up to the early part of the fourth-century” (Aland 53-54 for the quoted portion). Given their predisposition to paganism, it is not surprising that these converts were slow to digest the pure truths that Paul preached, as evidenced by their inclination to subvert the Gospel by way of its redefinition along syncretic lines, that is, to change the Gospel in such a way as to make it consistent with the claims of the mystery religions, or Stoicism, or Gnosticism, etc. As the Jewish Christians endeavored to incorporate their Judaism into Christianity, so too the Gentile Christians endeavored to incorporate their paganism into Christianity; and here each was helped by the subversion of false teachers. Thus the prominent tenets of Christianity became blurred and "redefined" in these instances. Both the Pauline and the Johanine texts reflect this struggle (e.g., Acts 20:29, 1 John 4:1-4). The verses in 1 John reflect the particular heresy of the day, especially in Asia Minor: misidentification of Jesus.

"Our view of the West and of Rome in the early Church has generally been unduly influenced by later history. Rome and Italy played a distinctly subordinate role in the early period of church history with regard to theological and scholarly interests [...]

There was certainly a church in Rome when Paul wrote his letter to the Romans. When the ship which brought Paul to Rome as a prisoner moored at Puteoli, he found a church already there as well. Further, the church in Rome continued to be significantly productive to the end of the second century and on through the first half of the third century, but this was mainly in the area of pastoral matters, particularly in practical theology: expanding the primitive form of the creed, contributing to a definition of the canon, developing the church practice of penance, and improving the church's administrative structure" (Aland 54).

We generally do not have a good understanding of how the Christian Church developed in Rome. The Church's establishment there is unclear—Paul certainly did not establish that Church, and the tradition holding that Peter established it is not altogether solid (Melton). A significant aspect about the Roman Christian Church is that is where Nero instituted the first state-sponsored persecution of Christians. The catacombs of Rome, located about three miles from the center of the city, and forming roughly a circle, were used by the early Christians as hiding places to escape the Roman persecution. The Eucharist, which accompanied funerals in the early Church, was celebrated there. It seems, however, that they were probably not used as secret meeting places for worship as is widely believed—space considerations preclude the accommodation of what is believed to be as many as 50,000 Christians in and around Rome in the period under study; furthermore, they were considered "unclean" not only in Jewish, but also in Christian circles ("Catacomb1," “Catacomb2,” Melton).

It is not altogether clear how or when Christianity became established in Egypt, or North Africa for that matter; there is no direct evidence of Christianity having existed in Egypt until Clement of Alexandria (AD 150-220). An uncertain tradition holds that Mark the Evangelist founded the Church at Alexandria. Luke tells us that Egyptian Jews were present at Pentecost (Acts 2:5-11); one can reasonably assume that some of these Jews were converted and started faith communities and/or churches upon their return to Egypt. In that vein, the early Egyptian Christians of this period were probably converted "God-fearers;" that is, pious Hellenistic Jews. One thing we do know with certainty here: by the middle of the second-century AD there were large and thriving churches both in Alexandria and North Africa (Aland 53-54), and the first Christian school of higher education was active in Alexandria—the prominent School of Alexandria. Under its earliest known leaders (Pantaenus, Clement, Origen) it became known for its allegorical method of Bible interpretation (over against the School of Antioch in Syria known for its literal method of Bible interpretation); the School of Alexandria sought also to reconcile Greek culture and Christianity in its teachings.

Diverse; this is the word that perhaps best describes the character of the Christian Church in the latter-third of the first-century AD. The argument for a monolithic "New Testament Church" is probably not tenable, not in this period and even later when universality of sorts became more evident (we mean that universality which became manifest as the Church moved ever further away from Jerusalem—true universality did not come until Constantine I became emperor and was converted in the early fourth-century AD). It is more accurate to argue for the existence of New Testament churches—plural—rather than a universal Church in this period (Melton). New Testament churches that derived from the faith community of which each was comprised, and so reflected the diversity peculiar to peoples and regions. The diversity of the centers of growth discussed above is a case in point—Christianity was not a "body politic" here. Another important force behind this diversity in the period under consideration is the absence of regulative norms, which were themselves only now coalescing, and would not be distilled, and authenticated, and finally enjoined, until well into the fourth-century AD (“New Testament Canon”), though two notable efforts toward that end would soon appear in the middle and near the end of the second-century AD—one heretical (Marcion’s Canon, c. AD 140) and one prototypical (Muratorian Canon c. AD 180). So the early Christian Church of this period could be characterized as having a wide variety of beliefs and practices and understandings of the Christian faith. Just next are discussed some of the characteristics and/or conditions particular to the Church in the period under study.

the Septuagint was produced as a consequence of the pervasiveness of the Greek language in the Diaspora, especially in Egypt, where the Jewish population had become quite large, and where therefore was felt a great need to have available to these Jews, who had gradually become illiterate in their native Hebrew, a means to interpret, in Greek, the reading of the Law in the synagogues. The language of the early Christian Church too was Greek; as such many early Christians turned to the Septuagint in order to study and interpret the Old Testament prophecies that had been fulfilled in Jesus. The Jews regarded this as a misrepresentation of the Scriptures and consequently stopped using the Septuagint—its practical history is therefore largely Christian. As some of the New Testament books were being written at this time (“New Testament Canon: Table 1”), the Septuagint undoubtedly became an indispensable reference for the New Testament authors as well.

The early Church's memory of Jesus' power, presence, promise, and resurrection fostered in it a heightened anticipation for His return (1 Thess. 2:19, 1 Thess. 4:13-18, 1 Thess. 5:1-3, 1 Thess. 5:23, 2 Thess. 2:1-12). Undoubtedly the persecution and suffering of the times helped fuel this anticipation, for it is an empirically evident fact of life that persecution and suffering fosters eschatological expectation in the soul. But there were living at this time still Christian men and women who had handled, and/or heard, and/or seen, the risen Christ—and their hope was more than an escape. It was Christ Himself that was the object of their hope, not transcendence. So the early Christians probably expected Jesus to return soon, given their fresh memories of His presence, His promise, their persecution and suffering, and the signs of the times (the wickedness of the Greco Roman world around them). It is not likely, however, that Paul, for example, expected Jesus to return imminently; that is, precisely within his lifetime. It is near sure, though, that Paul and many other Christians realized that the advent of Jesus in human history was also the advent of the eschatological age, and that meant, in no uncertain terms, that He could come back at any moment—like a thief in the night (1 Thess. 5:1-4), unexpectedly (Melton). As the decades of the first-century AD went by Christians began to realize that some adjustment in their expectation was necessary; the end of the age was not going to come in as quickly as they likely thought. They realized therefore that they were going to have to settle down in the world and organize themselves—under the guidance and lead of the Helper, the Holy Spirit, Whom Jesus Himself had sent for such purposes—and get busy doing the task which Jesus had commissioned them to do; that is, evangelize all peoples, everywhere, across time (Matt. 28:19-20), until He finally brought in the End.

As mentioned above, the setting of the great fire of AD 64 which consumed Rome was pinned on Nero by the Roman populace. In response, he shifted the blame to the Christians. Thus began the first state-sanctioned persecution of Christians. It is likely that the persecution was generally contained to Rome and its surroundings. The persecution under Domitian (AD 81-96) was altogether different however. Domitian was the second son of the emperor Vespasian (AD 69-79) and the brother of the emperor Titus (AD 79-81; Tab. 3). He fancied himself to be a god and enforced empire-wide worship of himself on Sundays.

"While Nero sought to use the Christians as a scapegoat to blame for the fire in Rome in 64 C.E. which he was suspected of setting, it was Domitian who first sought to force Christian observance of the imperial cult. Coins proclaimed Domitian 'father of the gods,' and he required those seeking an audience to address him as 'our lord and god.' He made participation in the imperial cult mandatory and used the observance as an acid test to identify 'enemies of the state'[...]

Most scholars believe that the persecution under Trajan was an extension of the savage treatment of Christians under Domitian and that the book of Revelation was written to support the suffering church" (Roetzel 74-75).

To round out this section it might be of interest to point out that there is no evidence of systematic, state-sponsored persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire after the reign of Domitian until the reign of Decius (AD 249-251). That is not to say that Christians were not under threat of martyrdom or other forms of Roman persecution in that period, for they certainly were. Localized, sporadic persecution that included confiscation of property, torture, and martyrdom occurred all throughout that roughly one-hundred-fifty-year period (“Christian martyrs”).

Most, if not all of the social, political, and religious value system that comprised Greco-Roman culture was diametrically opposite to the same Christian values; as such Christians tended to keep to themselves. Furthermore, a Christian's prime motivation was allegiance and servitude to Jesus Christ, first and foremost, not Caesar. This mindset became a difficulty for Christians in their relationship with Rome; a difficulty which probably began to surface sometime before AD 64 when the first persecutions began under Nero (Melton). One has to wonder why he singled out Christians to be the scapegoats for the fire he likely set.

"The Roman authorities viewed Christians as subversives who threatened the established social order. There is some evidence that despite the absence of a systematic crusade, there was an understanding by Roman leaders that Christianity was something more than just another branch of the legally approved religion, Judaism, but was in fact an illegal cult and that to be a Christian was per se a serious criminal offense" (Niswonger 274).

The issues at hand all throughout the first-century AD in this regard were both internal and external to Christianity (Melton). Internally, two issues persistently tested the Church:

(1) Whether or not Christians were required to yield to circumcision in order to become full-fledged members of the Church (this issue with respect to women is addressed in III.B.7 and the subject of baptism).

(2) To what degree a Christian was to embrace the Law.

The Jewish wing of the Church essentially stressed full compliance on both points; the Gentile wing adopted a more libertine perspective. The problem the Church faced here was a complicated one. Christians realized that Jesus had made salvation a matter of grace; grace available simply by faith in Him, thus obviating the Law (Gal. 3:24-25). But Gentile Christians tended to interpret this grace as a license to live a libertine lifestyle; in these cases that lifestyle reflected the paganism from which they had been converted. How was the Church to communicate Christian living to these converts without at the same time communicating legalism—legalism that the Jewish missionaries were preaching aplenty? We understand today that Paul anticipated these issues in his letters, particularly in his letters to the Romans and to the Galatians. So internally the Church came under strain through the issue of conformance to Judaism’s principles; this could essentially be summarized as a question of the reach of, particularly the Law, as also the traditions, in a Christian's life. Externally, the issue for the Church was twofold. First there was the matter of competition (Tab. 4). As the table points out, Christianity was at a significant disadvantage in its missionary quest against Judaism until the fall of Jerusalem. At that point the tables turned however. Second there was the matter of persecution at the hands of the Jews. Whereas Jewish Christians could be both Jewish and Christian as far as Judaism was concerned in the years AD 33/34-65, they could not be both by the latter-third of the century. In fact, Jewish Christians were expelled from the synagogue and were disowned by both family and friends (anathema) when they were found out to be Christians. So the Christians' external clash with Judaism came by way of missionary competition and persecution at the hands of Jews.

The further the Church removed from the narrow, provincial, Jewish backdrop of Jerusalem and Palestine, the more universal it became in scope (Melton). Legalism and formalism gave way to Grace. And a sense of community—over against the exclusiveness of the Jewish Dispensation—came in. Christianity is the first religion that was intended for all peoples alike; prior to Christianity no such notion existed (Joyce). Jew and non-Jew, all races, all nationalities, are welcomed by the Christian Church, all become brethren in Christ. Jesus Himself signalized this by His own actions—the first evidence of the universality of the Gospel can be seen when Jesus befriended the Samaritan woman at Jacob's well (John 4:1-9).

"Now it is the essence of Christianity that it is to be had for the asking. It is perfectly at home on the beach at Blackpool or anywhere else. The joy which Christ repeatedly promised His disciples was, and is, universal and popular. It is for children as well as for adults. Indeed, it is pre-eminently for children, 'for of such is the kingdom'" (Green-Armytage 163). So as the Church spread out into the Hellenistic world it became more universal and community oriented.

Realizing that it would be in the world longer than it first thought, the Church began to organize itself in order to more efficiently carry out the commission that Jesus had given it. We can see a form of this organization by looking at the New Testament itself (1 Cor. 12:28, Acts 20:28, Heb. 13:17; cf. Fig. 3). In the same vein, the Pastorals give specific instructions to local church elders (also called bishops, overseers, and presbyters; the Greek root word is EPISKOPOS, literally, "overseer;" it connotes the same as do "curator," "guardian," "superintendent/supervisor"—1 Tim. 3:1-5, Titus 1:5, Titus 1:7; note also Phil. 1:1, 1 Pet. 5:1-3). As time went on and Church membership grew, ministerial activity grew commensurately—the tasks became more numerous and complicated. Thus organizational structure was a practical way to meet those challenges; it helped get things done, then as now. There was at this time, however, no superstructure organizational pattern that all churches throughout the Roman Empire copied—if such a pattern did exist, it was highly fluid, at best (Melton). It must be remembered that there existed no New Testament Canon at this time (Muratorian Canon came near the end of the second-century AD, the authoritative New Testament Canon near the end of the fourth-century AD). The writing of the Scriptures referenced above was in flux and the grouping of the same would not come until later (“New Testament Canon”). Early Christendom as represented in this study had no governmental type documents by which to organize itself. Local church organizational structures likely varied as a function of those that best met the local community needs and/or heresies that pressed the churches into action (Melton). The congregations throughout the Roman Empire were not here all organized the same way, they were diverse. The idea that there existed an organizationally monolithic "New Testament Church" in the period under study is unlikely; admittedly, the substance and history of the early Church's organizational structure is a matter of some debate; a sampling of some organizational perspectives follow. The originating author is A. V. Hove, who is cited at the end of the excerpts.

"Holtzmann thinks that the primitive organization of the churches was that of the Jewish synagogue; that a college of presbyters or bishops (synonymous words) governed the Judaeo Christian communities; that later this organization was adopted by the Gentile churches. In the second century one of these presbyter-bishops became the ruling bishop. The cause of this lay in the need of unity, which manifested itself when in the second century heresies began to appear. (Pastoralbriefe, Leipzig, 1880.)[...]

Hatch, on the contrary, finds the origin of the episcopate in the organization of certain Greek religious associations, in which one meets with episkopoi (superintendents) charged with the financial administration. The primitive Christian communities were administered by a college of presbyters; those of the presbyters (sic.) administered the finances were called bishops. In the large towns, the whole financial administration was centralized in the hands of one such officer, who soon became the ruling bishop (The Organization of the Early Christian Churches, Oxford, 1881)[...]

According to Harnack (whose theory has varied several times), it was those who had received the special gifts known as the charismata, above all the gift of public speech, who possessed all authority in the primitive community. In addition to these we find bishops and deacons who possess neither authority nor disciplinary power, who were charged solely with certain functions relative to administration and Divine worship. The members of the community itself were divided into two classes: the elders (presbyteroi) and the youths (neoteroi). A college of presbyters was established at an early date at Jerusalem and in Palestine, but elsewhere not before the second century; its members were chosen from among the presbyteroi, and in its hands lay all authority and disciplinary power. Once established, it was from this college of presbyters that deacons and bishops were chosen. When those officials who had been endowed with the charismatic gifts had passed away, the community delegated several bishops to replace them. At a later date the Christians realized the advantages to be derived from entrusting the supreme direction to a single bishop. However, as late as the year 140, the organization of the various communities was still widely divergent. The monarchic episcopate offers its origin to the need of doctrinal unity, which made itself felt at the time of the crisis caused by the Gnostic heresies[...]

J. .B. Lightfoot, who may be regarded as an authoritative representative of the Anglican Church, holds a less radical system. The Primitive Church, he says, had no organization, but was very soon conscious of the necessity of organizing. At first the apostles appointed deacons; later, in imitation of the organization of the synagogue, they appointed presbyters, sometimes called bishops in the Gentile churches. The duties of the presbyters were twofold: they were both rulers and instructors of the congregation. In the Apostolic age, however, traces of the highest order, the episcopate properly so called, are few and indistinct. The episcopate was not formed from the Apostolic order through the localization of the universal authority of the Apostles, but from the presbyteral (by elevation). The title of bishop originally common to all came at length to be appropriated to the chief among them. Within the period compassed by the Apostolic writings, James, the brother of the Lord, can alone claim to be regarded as a bishop in the later and more special sense of the term. On the other hand, though especially prominent in the Church of Jerusalem, he appears in the Acts as a member of the body. As late as the year 70, no distinct signs of episcopal government yet appeared in Gentile Christendom. During the last three decades of the first century, however, during the lifetime of the latest surviving Apostle, St. John, the episcopal office was established in Asia Minor. St. John was cognizant of the position of St. James at Jerusalem. When therefore, he found in Asia Minor manifold irregularities and threatening symptoms of disruption, he not unnaturally encouraged in these Gentile churches an approach to the organization, which had been signally blessed and had proved effectual in holding together the mother-church of Jerusalem amid dangers no less serious" (Hove).

Whichever one or perhaps combination of these perspectives may hold, it is good to remember that our New Testament Canon came much, much later; the Church government we see in the Pastorals and elsewhere in the New Testament today may have been written and even been circulating amongst the churches at this time, but it was definitely not an authoritative standard as yet. This gave the various churches throughout the empire some leeway in the matter and bodes well for some degree of diversity at this time. The argument for a "one size fits all" New Testament Church in this period seems altogether untenable.

Early in the Book of Acts worship appears to be informal and spontaneous (Acts 1-3). There does not seem to be any set liturgy (form, order, or structure of worship); no formal master pattern of worship must have existed. In course of time three points of Jewish worship significantly changed that. The Passover ritual became reflected in the Lord's Supper, the synagogue service, with its Bible readings, prayer, and sermon, formed a model for early Christian services, and Jewish proselyte baptism served as a pattern for Christian baptism. It must be said here that while the Jewish parallels inherent in the Christian rituals are considerable, the Lord’s Supper and Christian Baptism were instituted by Jesus personally and must be acknowledged to have come from Him alone. (1 Cor. 11:23-26, Matt. 28:19-20).

For the most part the first believers met in the Upper Room or at one another's houses or in the temple courts. The apostles taught what they knew about and had heard from Jesus, and the believers devoted themselves to the apostles' teachings. They broke bread and ate together and shared all things in common. And as many as believed the Gospel that was being preached were baptized into the Body of Christ.(Acts 1:12-14, Acts 2:41-47). Baptism, celebration of the Lord's Supper, group prayers, teaching, and a general sense of camaraderie and fellowship largely characterize worship in the early period—again, Jesus did but institute two rites: the Lord's Supper and Baptism, and these two became attached to Christian worship from the beginning, and have remained until today. In the latter third of the first-century AD, as concerns us here, worship began to take on a more regular, formal pattern. In this time frame some New Testament documents were still being written, so any New Testament text that conveys to us aspects of worship more than likely represents mid to latter-third first-century AD worship patterns (“New Testament Canon: Table 1”). It does not appear that there was a single, universal liturgy that was adopted by the various churches and faith communities at this time; the liturgy was probably varied, much like it is still today. Notwithstanding, there were some points that all churches generally had in common. Worship was on the first day of the week, mainly as a way to call to recollection our Savior’s resurrection. There was singing (Eph. 5:19, Col. 3:16) of hymns and psalms (the word psalm used in the New Testament comes from the Greek verb PSALLW which means pull off, pluck out, cause to vibrate, sing to the music of a harp, play the harp, etc.; it is near sure that musical instruments—undoubtedly stringed—were part of early church worship). Churches regularly celebrated the Lord's Supper, as said, but there was no set frequency to that celebration. They obviously prayed in worship, and they apparently read from Paul's letters which were by now circulating. They read from those gospels to which they had access (themselves either written or being written in this period). They observed regularly Christian Baptism; baptism was always done in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, and symbolized entry into the Christian Church. Christian baptism was the Christian parallel to Jewish baptism and circumcision; it was the visible sign that a believer was entering into the New Covenant, much like Jewish baptism, and to a lesser degree, circumcision, were visible signs that a Jew was entering into the Old Covenant. In consideration of this, one may take a look at the rite of entry into Judaism, because like the case for entry into Christianity, that was pre-eminently baptism—in Judaism, circumcision and the act of the sacrifice (the bringing of the first-fruits into the temple Deut. 26:10) were secondary and supplemental, respectively. Circumcision was secondary in that it was not applicable to women–only baptism practically applied to both men and women, and the act of the sacrifice was supplemental in that it was understood to be the first act of worship after admittance into Judaism. It could be argued that Jewish baptism was singularly Levitical, that is, crudely purificatory (sin cleansing), whereas circumcision, like Christian baptism, was manifestly spiritual and sacramental; if that were the case, however, women converts could not have entered into the Old Covenant, and it is likely they were more numerous than the men converts. It is for this reason—the rite of conversion as applied to women—that proselyte baptism became the pre-eminent rite of conversion within the Judaism of New Testament times (Daube 106). And it was understood that what was effective for women must necessarily be effective for men, hence baptism made even males manifestly Jewish. The rabbis had a saying, ‘he who separates himself from the uncircumcision is like he who separates himself from the grave.' We clearly know that Hillel applied the saying to both men and women converts. Heathenism, then, was compared to living in a tomb, and the rite of conversion—Baptism—was compared to separating from the grave, or in other words, a passage from death to life. These are spiritual ideas, not Levitical ones. As David Daube points out, the Judaism of the day utilized Levitical ideas simply to reinforce and explicate the spiritual ones. Within Judaism proselytes were like men and women who had risen up out of their graves. Therefore, symbolically, the decisive moment in Jewish proselyte baptism was the coming up, or the rising up, out of the water. When Jesus was baptized both Matthew and Mark expressly draw attention to the instance of His coming up out of the water, for it was then that the heavens were opened and the Holy Spirit descended on Him (Matt. 3:16, Mark 1:10). What we see here is one good indication that the form of Christian baptism possibly originated in Jewish proselyte baptism (which form John the Baptist and hence Jesus was following). As further evidence, the rabbis of the New Testament period generally considered a convert (on the basis of baptism alone, even a woman) to be a new-born child; the "newness" was astonishingly far reaching (Daube 112). New birth by way of baptism was taken very seriously within Judaism; that is, it was expressly associated with the rite. Again, the idea of new birth, akin to the passage from death to life discussed above, is not in the least Levitical; rather, it is a highly spiritual idea and is not unlike the Christian concept (for more background here see Daube 106-38; cf. John 3:1-10).The Didache, written near the end of this period, and reflecting a Jewish form of Christianity, suggests that practicality more than ritual may have governed the form of early Christian baptism (Did. 7:1-7). Jewish proselyte baptism, the Passover ritual, and the synagogue service profoundly influenced the development of Christian worship services as related by our New Testament.

"Already in the New Testament—apart from the account of the Last Supper—there are some indexes that point to liturgical forms. There were already readings from the Sacred Books, there were sermons, psalms and hymns. 1Ti 2:1-3, implies public liturgical prayers for all classes of people. People lifted up their hands at prayers, men with uncovered heads, women covered. There was a kiss of peace. There was an offertory of goods for the poor called by the special name 'communion' (koinonia). The people answered 'Amen' after prayers. The word Eucharist has already a technical meaning (ibid.). The famous passage, 1Cr 11:20-29, gives us the outline of the breaking of bread and thanksgiving (Eucharist) that followed the earlier part of the service. Hbr 13:10 (cf. 1 Cor. 10:16-21), shows that to the first Christians the table of the Eucharist was an altar. After the consecration prayers followed. St. Paul 'breaks bread' (= the consecration), then communicates, then preaches. Acts ii, gives us an idea of the liturgical Synaxis in order: They 'persevere in the teaching of the Apostles' (this implies the readings and homilies), 'communicate in the breaking of bread' (consecration and communion) and 'in prayers'. So we have already in the New Testament all the essential elements that we find later in the organized liturgies: lessons, psalms, hymns, sermons, prayers, consecration, communion" (Fortescue).

So the New Testament documents, written or being written during the period under study, show us that by now worship in early Christendom took on patterns that have largely persisted across the centuries.

"The earliest writings to be collected were probably the letters of Paul. Each of the churches having one or more letters from the apostle would not only preserve them carefully, reading them when they assembled for worship, but would also exchange copies of their letters with neighboring churches. This is the only possible explanation for the preservation of the Galatian letter, since the church(es) addressed in it did not survive for long[...]

When the church in Rome sent a formal letter to the church in Corinth about A.D. 95 (known as 1 Clement, the earliest Christian document outside the New Testament), not only did it include references to Paul's letter to the Romans (as might be expected), but also clear citations from 1 Corinthians and Hebrews. This must reflect the existence in Rome at this time of a collection of Paul's letters, although its extent cannot be determined precisely because the quotations and allusions to other letters of Paul cannot be identified conclusively. In Marcion about 140 we find definite quotations from Galatians, both Corinthian letters, Romans, both Thessalonian letters, Ephesians (which he knew as the letter to the Laodiceans), and the letters to the Colossians, Philippians, and Philemon—this was evidently the order of the Pauline letters in the manuscripts used by Marcion. The Muratorian Canon adds to these the Pastoral letters about 190. The letter to the Hebrews does not appear in either (it was rejected by Marcion because of its Old Testament associations, and by the Muratorian Canon because of its denial of a second repentance [Heb. 6:4-6]). The earliest manuscript of the Pauline letters, p,46 dating from about 200, includes it (the early Church assumed Hebrews to be Pauline); unfortunately the text breaks off at 1 Thessalonians, so that it is unknown whether 2 Thessalonians, Philemon, and the Pastoral letters were originally included. Unlike the Gospels, the letters of Paul were apparently preserved from the first as a collection. At first there were small collections in individual churches; these grew by a process of exchange until finally about the mid-second century the Pastoral letters were added and the collection of the fourteen Pauline letters was considered complete. From that time it was increasingly accorded canonical status (with the exception of Hebrews, which the Western church refused recognition until the fourth century because of its rejection of a second repentance)" (Aland 48-49).

Aside, E. R. Richards has suggested that the collection of Paul's letters may have been more or less straightforward; he cites evidence from Cicero (Letter to Friends 9.26.1) which reveals that it was probably normal for a secretary (to which Paul would have availed himself whenever possible) to make two copies of a letter, one of which was retained by the sender (Richards 165n. 169)- (Witherington-Paul Quest 102n. 89-129) . So we see in this period the probable composition of many of the books of the New Testament, and the onset of a process of New Testament canonization which would last for nearly three centuries. See also New Testament Canon.